The Fat Belly every master has to go through

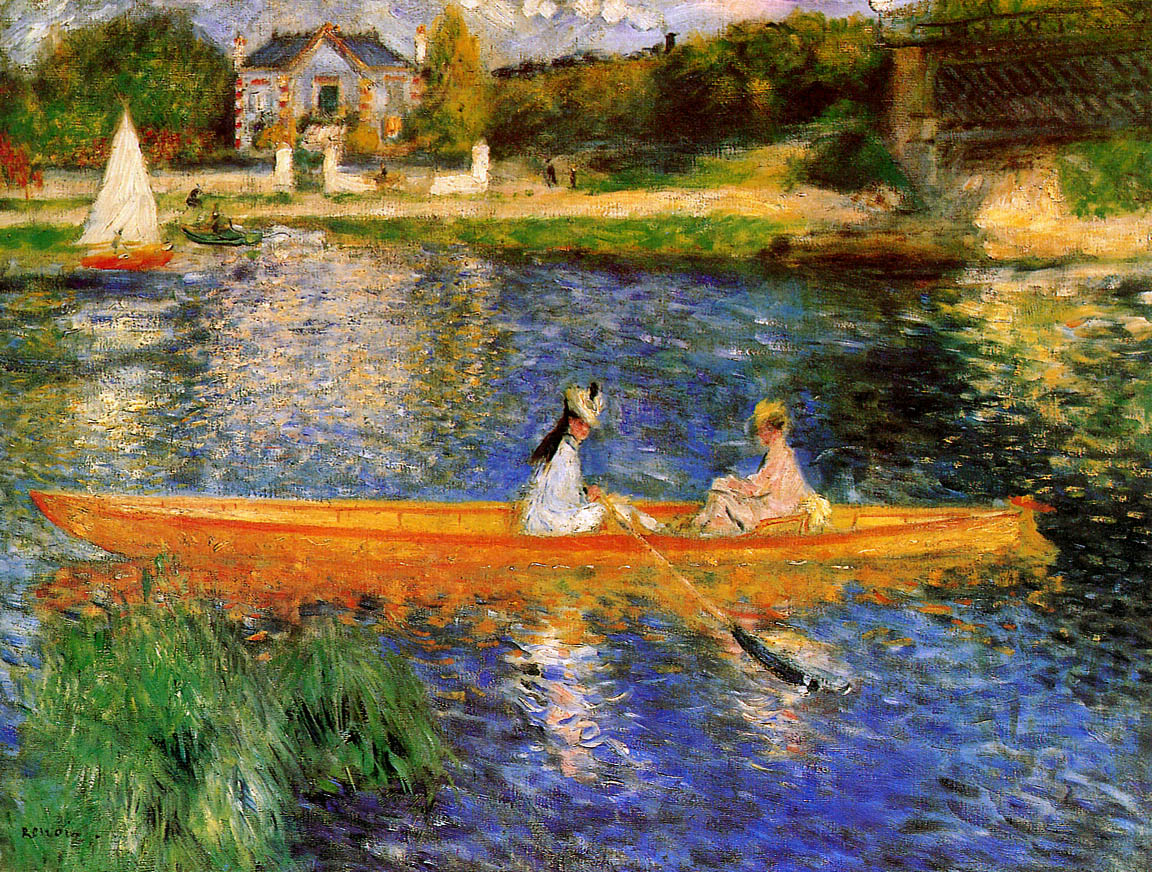

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a master of color.

Just take a look at his 1875 piece titled The Skiff (La Yole) and you can see for yourself:

Do you want to know something really cool?

He made this with only eight paints — and one of them was white.

Contrast this with the 50+ bottles of pigment I use to paint my little plastic toy soldiers:

Renoir painted one of the most famous Impressionist paintings with eight colors — I painted a goblin’s nose with five. Which is A) funny, and B) makes it clear that Renoir could create a much better piece with much fewer tools than I can.

One answer to this would be to point out that Renoir is one of the best painters who ever lived, while I’m a literal nobody. Which is fair. But I think there is a more general — and exciting — idea at play here.

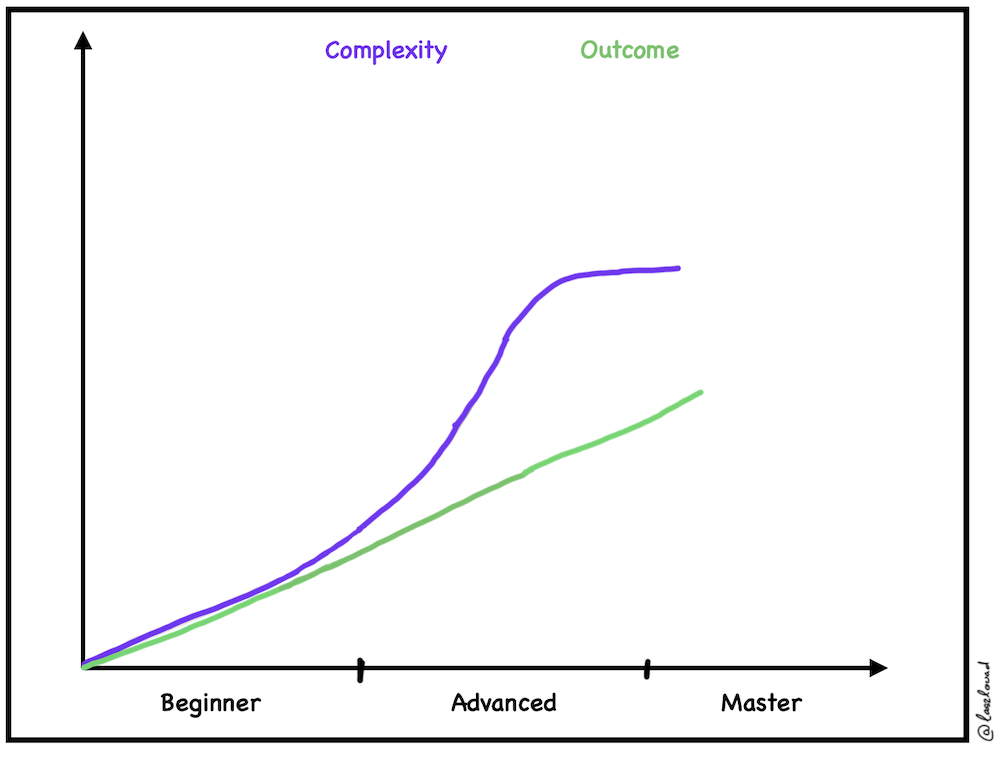

In my head, I call it the Outcome/Complexity curve.

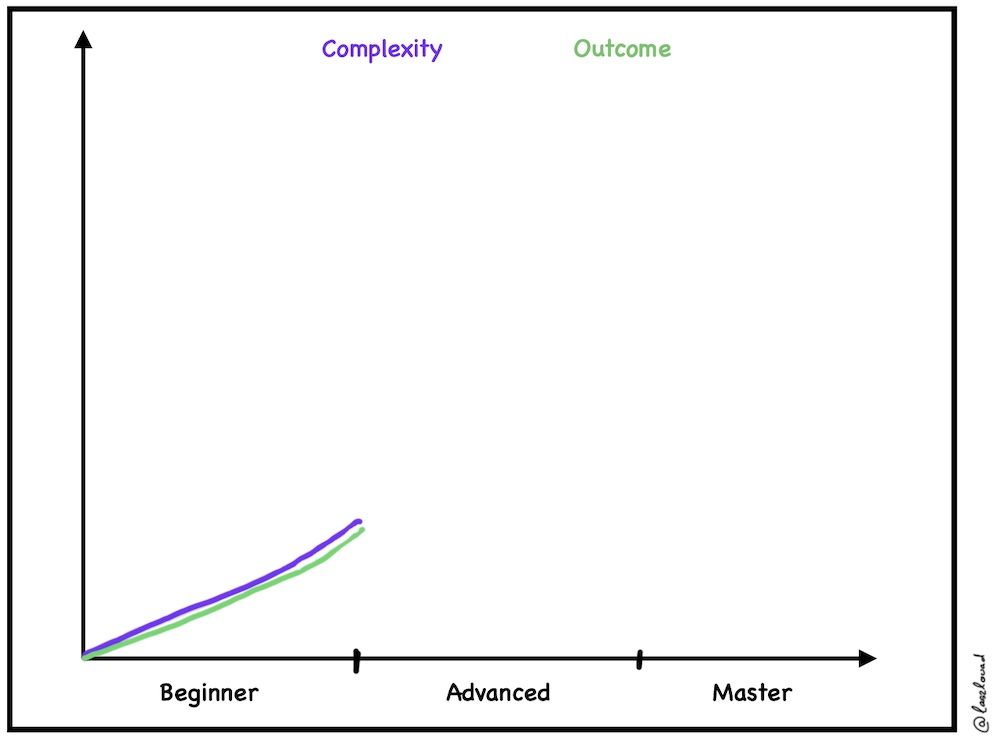

When you start out learning a new skill, the complexity of your tools and skills hovers around zero. It’s easy to draw a goofy-looking stick figure, make a computer print “Hello World”, or assemble a sandwich. You’re not doing anything amazing, but you’re also not really breaking a sweat.

You’re here:

In this beginner phase, complexity and outcome move in lockstep. You apply a little more effort, and you get a bit better results, but everything remains pretty chill.

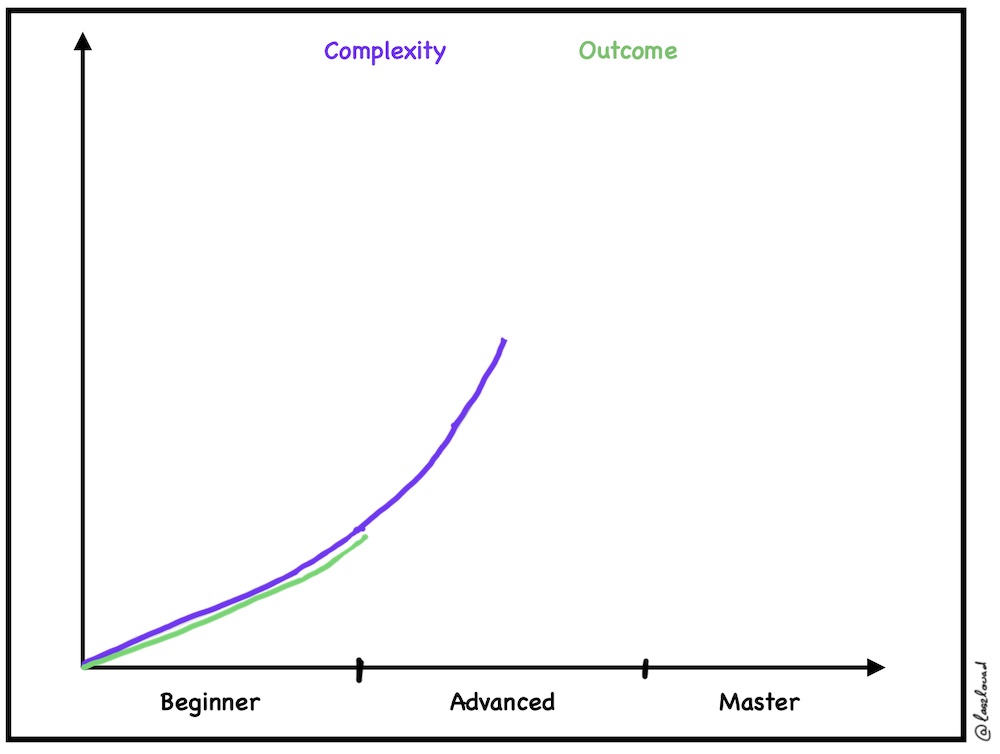

Then, as you get more and more into your new thing, at a certain point you realize how much you don’t know. You find out there’s a whole world of tools and techniques you could use to achieve dramatically better results.

You learn of drawing boxes in 3D space to break down complex anatomies into simple shapes. You enroll in Harvard’s CS50 course and get deep into the basics of computer science. You buy a really good culinary science book and start constructing and deconstructing flavor profiles.

At this stage, you massively hike up the complexity you’re trying to manage.

Usually, this is also the time when you buy a ton of stuff, trying to convince both yourself and anyone who listens that these new shiny things will make you a better artist/programmer/chef, etc. (Pour one out for our ever-patient and supportive spouses and partners.)

The complexity line goes up:

But what about the outcome?

Well, it increases, but a bit differently.

Don’t get me wrong, your drawings are definitely getting better. You share a few on Instagram and the likes and comments pour in. Some of your friends even ask if you sell prints.

You write a simple program to take care of the tedious monthly budgeting for you. Sure, the UI is sparse, and the code sometimes breaks on weird edge cases, but more often than not it works and saves you a ton of time. You deploy it to a website and a few dozen people download it. One of them even sends you ten dollars to the tip jar you linked.

You invite your friends over to dinner once every month to show off the new dishes you dream up after work. Every time you do this, they tease you to quit your job already and open up a sandwich shop.

You start to like your outcomes but also begin to chafe against the time and resources you need to spend to achieve them. Your complexity increases exponentially, while your outcomes follow only linearly:

Right about here, things tend to diverge.

Some of us will decide that our thing — be it drawing, programming, sandwiches, or something else entirely — isn’t worth this much effort. We scale back your hobby to a level of complexity vs. outcome we can comfortably manage and stay there. Probably for the rest of our very sane and very happy lives.

Then there is the other group.

The maniacs who say fuck it — in for a penny, in for a pound.

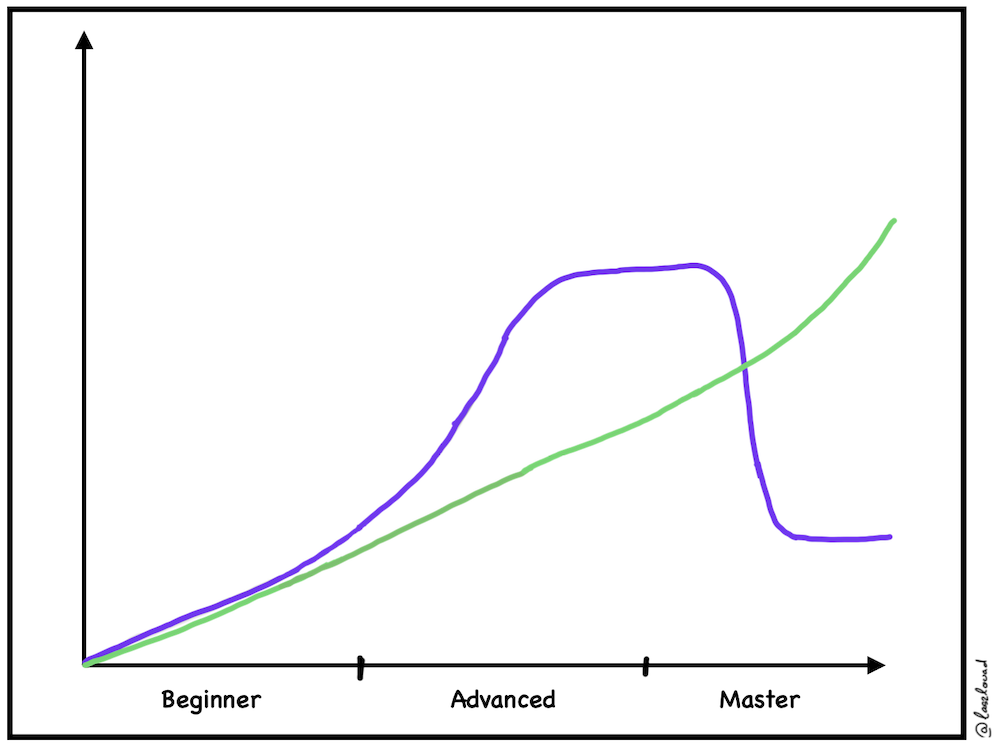

These people will start to keep pushing the complexity curve, but now with a very specific question in mind:

What are the things I must learn to have the results I want?

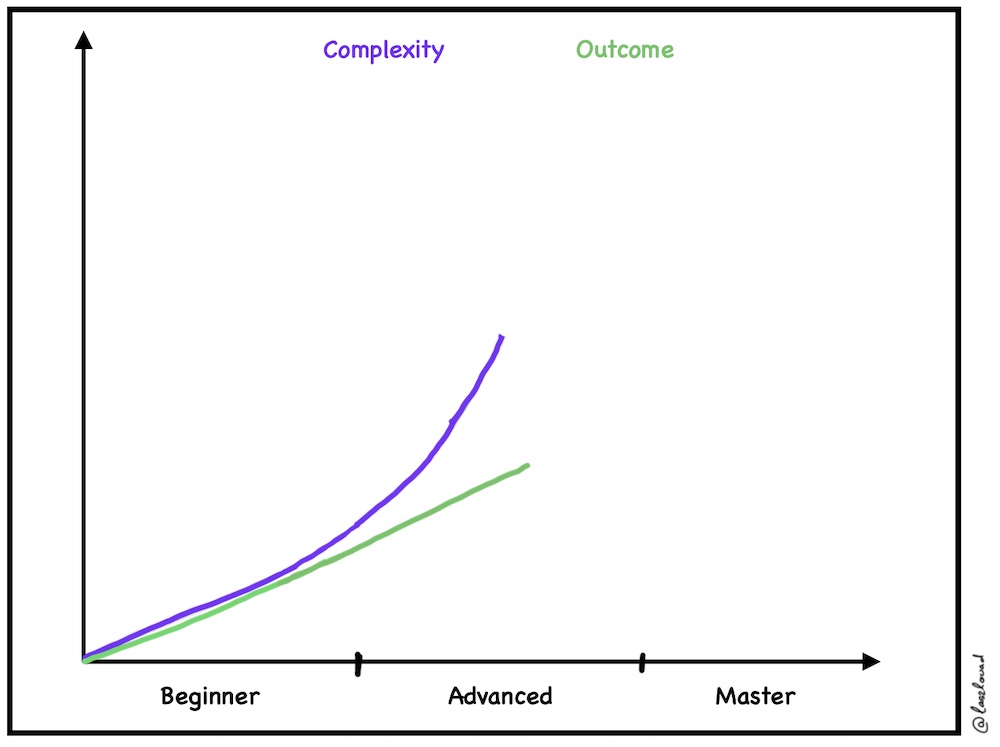

If you’re part of this second group, you’ve already seen all you could learn and realized that a lifetime wouldn’t be enough to do it. You also recognize that you only need some of this gargantuan knowledge base to bring your vision to life. So you zero in on those missing skills, and ignore the rest.

This approach, slowly, but surely flattens out the complexity curve, while the quality of the results continues to rise:

And then, at the plateau, you switch questions:

What can I eliminate, but still keep the level of quality?

I think this question marks the first step you take into true mastery.

This is when you start to get rid of all the unnecessary paints and hone in on your eight bottles. This is when you drop the myriad of programming frameworks and define the few developer tools you actually depend on. This is when you sell the two kitchen’s worth of equipment, but buy a really expensive grindstone for your best chef’s knife.

You relentlessly push complexity down, while your outcome — somewhat counterintuitively — will continue to rise, and even accelerate.

This is when you invert the graph and get to paint The Skiff:

You probably heard the phrase — or even said it yourself — that professionals make whatever they do look easy. (Just watch Gordon Ramsay fillet a salmon.) Only when you try to emulate them do you realize how hard what they’re doing really is.

I think the Outcome/Complexity curve explains why that is.

True masters know their craft well enough to know which eight bottles of paint they need out of the thousands. And they also know how to wield those eight bottles.

So, what’s the moral of the story?

The first time I articulated this particular idea, it gave me two handholds for practicing art:

One: Complexity of outcome doesn’t necessarily mean complexity of process.

I think this is a powerful realization. I don’t get discouraged anymore when I see something that looks ridiculously intricate and hard. Instead, I get excited, because I know that there is some relatively simple process of how the artist achieves the outcome.

Yes, it almost certainly took them hundreds and hundreds of hours to figure it out, but given enough time and deliberate practice, I can find the same “simple” process and replicate what they are doing.

Two: There is no skipping the Fat Belly of the curve.

I cannot hack myself into the master territory without going through the complexity gauntlet in the middle. It’s not only okay to buy 50+ bottles of paint while I’m figuring out what will be the eight I really need, but necessary. I can only pare down and polish my process if I let myself go wide and learn what is there in the first place.

When I started out running D&D games for my friends, I regularly spent 9+ hours for every 3-hour session. When we finished our big campaign last year, I prepped 1-1.5 hours per session on average. And I think if you’d ask my friends, they would say those later games were much better, much more intricate than the ones I spent 9 hours on.

So now that I’m in the Fat Belly of my painting journey, I happily spend 30-50 hours on a single figure, because I know this is only temporary. As I get better, the time and the complexity will go down, and eventually, I’ll get to invert the graph.

Anyway, I guess all I’m trying to say is that there are magical things we humans can do — but we are never magic. If you want to learn something, you can.

And also, go to a Renoir exhibit.

That dude was fire.