English is just badly pronounced French

If you want a surefire way to rile up a British nationalist, just mention the French.

For example, check out this gentleman — a disillusioned former Leave voter — when a reporter asks him whether he regrets voting for Brexit:

Reporter: Do you say you regret voting to leave?

Gentleman in the (German) Adidas jacket: Partially, yeah. A little bit. But there are bits that… I.. I can’t get past France and Germany. Don’t like them. I never have done.

You could probably sneer and say: “Oh well, that’s nationalism for you. Nationalists are xenophobes who hate everyone.”

But you’d be wrong.

The same gentleman in the same interview speaks quite fondly about their mixed-nationality neighborhood and especially the delightful Romanian family living next door. He just really can’t stand the French and the Germans — specifically.

He’s also not alone.

Redfield & Wilton Strategies — a pollster based in London — has been tracking British sentiment toward the French since November 2021. Their latest numbers show that as of July 2023, 15% of Britons still hold an “unfavourable” view of France.

I wonder whether those people know just how much French they are speaking every day.

Yes, French.

Let’s wind back the clock a thousand years.

It’s 911, and the reigning French king, Charles the Simple, allows a group of ferocious Vikings to settle in Normandy. He doesn’t do this out of the kindness of his heart, but because the same Vikings had been burning and looting West Francia for the past three decades, and in their last raid, they even tried to sack the city of Chartres.

Although the Vikings were summarily defeated below the city walls, the king — and his clergy — thought it was better to grab the opportunity now and turn their enemy into an ally. So Charles gives the city of Rouen and the surrounding lands to the Vikings and makes their leader, Rollo, the first Duke of Normandy. In exchange, the Vikings convert to Christianity and pledge fealty to the French king.

And thus, the Normans were born.

Almost a hundred years later, Normandy is a successful territory of France, and the Norman nobility is busy embedding itself into Europe through marriage. As part of that effort, the reigning duke — Richard II — marries his daughter, Emma of Normandy to the English king, Æthelred the Unready.

By the way, can we take a second and appreciate how downright hurtful these noble nicknames are? I mean, hilarious, sure, but also… not nice?

And if you think that maybe Æthelred at least deserved it or something, you’d be wrong. As it turns out, it was just good old-fashioned schoolyard name-calling:

[Æthelred’s] epithet comes from the Old English word unræd meaning “poorly advised”; it is a pun on his name, which means “well advised”.

Jesus. Well, at least he wasn’t called that to his face:

Because the nickname was first recorded in the 1180s, more than 150 years after Æthelred’s death, it is doubtful that it carries any implications as to the reputation of the king in the eyes of his contemporaries or near contemporaries.)

Anyway, back to the story:

Æthelred marries Emma, and they have a son, Edward. Later, he’ll earn a much better nickname than his father — Edward the Confessor —, and after a bit of exile in Normandy, he ascends to the English throne in 1042. He does this with the heavy support of the Norman side of his family, so Normandy becomes pretty involved in the affairs of England.

Edward rules for twenty or so years, then dies without an apparent heir. Which throws the English court into chaos, but as we’ve learned from Littlefinger, “chaos is a ladder.”

And by that time, Edward’s Norman second cousin once removed, William the Bastard became really good at climbing ladders.

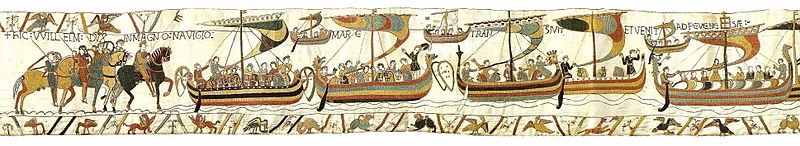

He assembles a rather formidable fleet and army and sails across the English Channel, landing on the Southeastern shores of the country. He swiftly erects a wooden castle and starts to pillage the surrounding lands. Lands that mostly belong to Harold Godwinson — the Earl of Wessex and the Englishman whom the Anglo-Saxons have already crowned king.

William’s strategy is a real asshole move, but it’s a brilliant one too.

Harold is occupied up North with another contender for the crown, and while he’s doing well there, he has to maintain a military presence to stay on top. So if he wants to come down to the South to deal with William, he has to divide his forces.

Win for the Bastard.

If he doesn’t and stays up North, William can cut him off from his lands and supplies, which in turn bolster the Norman army.

Also a win for the Bastard.

Some people are just better at climbing ladders.

Backed into a corner, Harold chooses to be bold. He takes a part of his army and rides south to meet William in battle at a town called Hastings, where — after a horrifying day of combat — he loses both the battle and his life.

This happens on the 14th of October, 1066.

Almost exactly two months later, William — the Conqueror — is crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey.

Although William’s rise to the throne is certainly interesting, what he did after becoming king is why we are talking about all of this in the first place.

To solidify his hold on the new country, he almost completely replaced the English nobility with Normans. Normans, who were loyal only to him, and who didn’t speak a lick of Old English. So French became the language of the ruling class and stayed that way for more than a hundred years.

And this is the reason why almost 30% of modern English words are actually French, and why today’s English speakers don’t have to contend with complicated sentence structures and gendered words. And this is why a few cheeky French like to say that:

The English language doesn’t exist. It’s all just badly pronounced French.

If the quick story above tickled your interest, I wholeheartedly recommend watching this YouTube video by RobWords.

Rob’s essay was where I first learned of English’s French connection, and he goes into a lot more detail than I did. Plus, he shares loads of fantastic linguistic tidbits along the way, like how English still displays the fossils of the Norman social structure with its word choices, or why some people still say “an historic” instead of “a historic.”

It’s a great video, I really do recommend it.